In his inaugural speech on May 29, 2023, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu echoed his mission under the ‘Renewed Hope Agenda’. Nigeria has seldom felt worse, as the depth of disappointment was at its peak. With unemployment reaching a high percentage people were desperate.

The message from newly elected President Tinubu was a restatement of how his administration would improve the people’s lives; strengthen bonds of economic collaboration; foster social cohesion and cultural understanding as well as develop a sense of fairness and equity.

Though it was not conceived as a campaign that will be anchored on arts, less than one year after the ‘Renewed Hope’ mandate, the gale of corruption, culture explosion, social tensions, rising ills, mischief, adult chauvinisms, hatred, demonic possessions, and violent politicking, among other social vices, have made the creative industry to attract new interest in deepening culture of honesty, transparency, governance beyond sophistry in age of ‘renewed hope’.

A film, song, theatrical enactment or piece or that interrogates honesty and lost tradition deserves attention. Nigerian classics deserve a look into. Not just because of adrenalin-pumping moments that culture missioners grapple with in modern society, but one that gives audiences reasons to take a refrigerator break for contemplation, especially in an age when films shape a child’s ideological leaning.

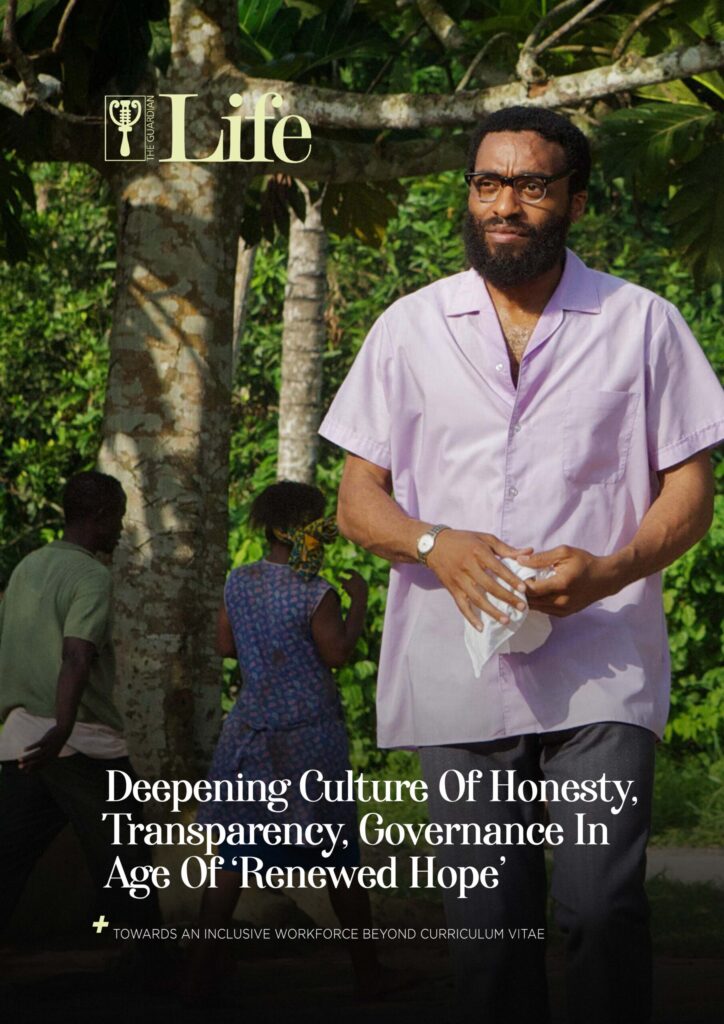

In the narratives of ‘Agogo Ewo’ and ‘Half of a Yellow Sun’, a profound exploration of Nigeria’s cultural and societal intricacies emerges, offering a nuanced reflection on the past and present.

‘Agogo Ewo’, a film steeped in the richness of Yoruba heritage, becomes a lens through which the erosion of essential values is lamented. Its narrative, unfolding against the backdrop of a fictitious state called Jogbo, intricately reveals the consequences of a lack of honesty, obedience, and trust within the intricate web of leadership.

The film’s portrayal of the kingmakers’ manipulation, driven by selfish interests, echoes a timeless theme of the misuse of power for personal gain. The intricate details, from dress codes to dialogue, serve as poignant reminder of the cultural treasures lost to the relentless march of time.

The late Adebayo Faleti’s role as an omnipresent narrator adds an anecdotal layer, exposing societal flaws through a lens that sees both what is and what should have been—a stark commentary on contemporary society.

‘Agogo Ewo’ may have been produced 22 years ago, every bit of the film demonstrates a lot of what the society lacks today: sense of history, culture, tradition, sincerity, honesty, obedience and trust.

Written by Akunwunmi Isola, with Tunde Kelani producing and directing, reflects today’s Nigeria and the need to morally win back the lost soul of the country in this age of ‘Renewed Hope’.

The film’s narrative is simple. Following the death of Lapite and Lagata, the Jogbo chiefs attempt to put an Onijogbo (king) of their choosing on the throne in order to be able to continue their corrupt practices. They pick a retired police officer named Adebosipo whom they thought will be in their favour.

On ascending the throne, Adebosipo turns a new leaf and decides to move on from corrupt ways and advocates for peace and progress in the community. He admonishes his chiefs to depart from their old ways. Balogun, Seriki, Bada and Iyalaje continue their corrupt practices.

The town youth kicks against the presence of corrupt chiefs on Adebosipo’s cabinet and call for their removal. The king sets up a committee to audit the activities of the chiefs. Those found guilty were compelled to return the funds looted by them. The king summons the Ifa priest Amawomárò, who recommends the reinstatement of an oath-taking ritual to ensure the moral upstanding of the chiefs.

A public oath-taking ceremony is organised and where the chiefs were to confess their past misdeeds before swearing the oath. Two chiefs, Balogun and Seriki, refused and died on the spot when the agogo eewo (taboo gong) was struck seven times.

The film juxtaposes Nigerian system of government with that of Jogbo. The film recommends that the tentacles of anti corruption agencies should cover every parastatals, ministries at national, state and local level, so as to curb the problem of corruption in Nigeria. It concludes with recommendation that penalties for corruption should be well listed in the Nigerian Constitution.

In a broader context, ‘Agogo Ewo’ becomes a cautionary tale for modern Nigeria, a nation grappling with economic, governmental, and societal challenges. The film’s relevance extends beyond its temporal origin, offering insights into the potential pitfalls of political leadership and the imperative for the youth to stand against prevailing issues.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s critically acclaimed novel, ‘Half of a Yellow Sun’, made its way to the big screen in 2013, directed by Biyi Bandele. This film stands as a poignant exploration of the Nigerian Civil War, while serving as a powerful commentary on the ills of the society portrayed within its frames. Set against the backdrop of one of the most tumultuous periods in Nigerian history, the movie seamlessly weaves together personal narratives with the larger socio-political landscape, shedding light on the devastating consequences of war, ethnic tensions, and the struggle for identity.

At its core, ‘Half of a Yellow Sun’ unravels the fabric of a society grappling with the complexities of post-colonial nationhood. The film navigates the early 1960s when Nigeria gained independence and subsequently plunges into a civil war owing to the secession of the Eastern region as the Republic of Biafra. As the narrative unfolds, it becomes a mirror reflecting the deep-seated issues that plague Nigerian society during this tumultuous era.

One of the central themes of the film is the corrosive impact of ethnic and tribal divisions. The deep-rooted tensions between the Igbo people and other ethnic groups are vividly portrayed, exposing the societal faultnlines that eventually escalate into a full-scale conflict.

The film does not shy away from depicting the brutal consequences of such divisions, as families and friendships fracture along ethnic lines, and a nation is torn apart by internal strife.

The film also sheds light on the socioeconomic disparities that fueled the conflict. Class distinctions and economic disparities become glaringly evident as the characters navigate the changing landscape of war. The stark contrast between the opulence of the elite and the stark realities of poverty faced by the common people exposes the systemic issues that contribute to the breakdown of societal structures.

‘Half of a Yellow Sun’ does not merely narrate the historical events of the Civil War; it meticulously dissects the societal ills that precipitated the conflict. It prompts viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about identity, tribalism, gender inequality, and economic disparities.

This is what Nigeria needs now a creative industry that will confront consequences of not doing the right thing, which has led to the philosophy of ‘Chop-I-Chop’ and ‘Share the money.’

“An evil man gives a bad name to his race, even when that race contains angels” is a popular saying, this, no doubt, is a reflection of the battle Nigerians face today, as they are tagged corrupt or using the words of former British Prime Minister, David Cameron, “they are fantastically corrupt”.

The country faces a moral battle to win its soul and a humanistic creative industry is what the country needs.

Though, there is a supposed proposition that inapt behaviours, nonchalant attitudes, moral decadence, and violence among children are outcome in most films produced in Nollywood films as espoused by Nkemakonam Aniukwu in the piece titled, ‘Nollywood and the leaders of tomorrow: Interrogating film content and character formation of the Nigerian child’, Nigeria needs a humanism of Soyinka that thinks of the future in ‘Death and The King’s Horseman’ and a quest for change and sustaining governance as seen in Fred Agbeyegbe’s ‘The King Must Dance Naked’.

In his ‘Ola Rotimi: The enduring influence of a Nigerian theatre giant’, Sanya Osha, Senior Research Fellow, Institute for Humanities in Africa, University of Cape Town, notes that “Rotimi viewed theatre as a way of building community both inside the theatre world and beyond. He saw theatre not as a closed and artificial art form but a way of connecting past, present and future. In this view, theatre serves as a link to the wider community and ultimately our common humanity.”

In plays such as ‘Our Husband Has Gone Mad Again’, ‘Kurunmi’, ‘Ovonramven Nogbaisi’ and ‘The Gods Are Not To Blame’, he focuses on moral dilemmas: good versus evil and right versus wrong, which Nigeria of today should be seeking answers to.

“After the curtains have fallen and the lights are out, the community beyond continues. And all – performers, singers, actors and dancers included – have to return to it. But they do not return to it, empty handed. They are supported by morals, ethics and a sense of social purpose and cohesion acquired during the play. It is the duty of each member of a cast to uphold and spread these ideals,” Osha says. “Rotimi’s humanism – like the southern African concept of ubuntu or the Tanzanian ujamaa – sees the collective rather than the individual as the predominant vehicle of social transformation.”

This humanism is what should push the Tinubu’s renewed hope agenda: The realisation of Africa’s cultural independence, the unification of continental Africa under democratic governance and Africa’s return to the traditional communalism of its ancestors.